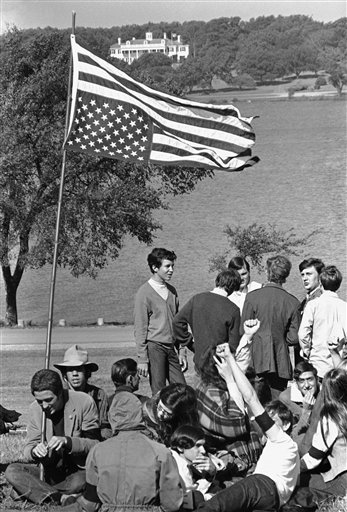

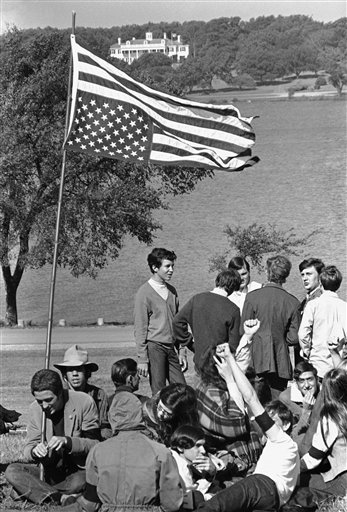

Flying the American flag upside down is sometimes done as a symbol of protest against U.S. policies. During the Vietnam War, a college student who flew a flag upside down to protest the Kent State shooting of Vietnam protesters was convicted under a state law against flag desecration. However, the Supreme Court overturned the conviction, ruling that his expressive conduct was protected under the First Amendment. In this photo, a group of people in 1969 in Dallas protest the Vietnam War (AP Photo/FK, used with permission from the Associated Press)

In the per curiam decision in Spence v. Washington, 418 U.S. 405 (1974), the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment protects the right to desecrate the American flag as a form of symbolic protest.

At the University of Washington in Seattle, Harold Omand Spence affixed peace symbols made of black tape to both sides of an American flag and hung it upside down from his dorm window to protest the 1970 incident in which four Vietnam protesters were killed by Ohio national guardsmen at Kent State University.

Spence was convicted of violating a state law prohibiting the placement of any “word, figure, mark, picture, design, drawing or advertisement” on an American or state flag.

The majority examined several factors in Spence that made it unique among flag desecration cases. Spence had owned the flag he displayed, and his dorm was located on private property rather than on government land. No permanent damage to the flag had occurred because the taped symbols could easily be removed. Finally, only the local police had objected to Spence’s flag protest, so community peace had not been disturbed.

Spence is often cited for the principle that an individual must show that he or she was intending to convey a particularized message with their expressive conduct in order to receive First Amendment protection.

In 1989, in Texas v. Johnson the Court once again upheld the right of symbolic speech when it overturned the conviction of Gregory Johnson for violating state law by burning an American flag on the steps of the Republican National Convention in Dallas to protest the policies of the Reagan administration.

The decision overturned existing state and federal laws on flag desecration, and an outraged Congress reacted by passing the Flag Protection Act of 1989. A group of protesters, including Johnson, challenged the new law by publicly burning a flag belonging to the Seattle Post Office.

Chief Justice Warren E. Burger and Justice Byron R. White joined Justice William H. Rehnquist in reiterating their dissenting position from three months earlier in Smith v. Goguen (1974), in which the Court upheld the right of a Massachusetts man to wear a flag emblem on the seat of his pants.

They supported the government’s interest in passing laws to protect American and state flags. Rehnquist insisted that the Court’s decision in Halter v. Nebraska (1907) was relevant to the constitutional issues raised by Spence. In Halter, the Court had upheld the right of Nebraska’s legislature to ban depictions of the American flag on beer bottles in light of half the states having passed laws banning flag desecration.

In United States v. Eichman (1990), the Court again upheld the right, 5-4, to desecrate the flag as symbolic speech. The majority adhered to the Johnson position, in which Justice William J. Brennan Jr. had argued that banning flag desecration violated the principles of the Constitution that the flag symbolized.

The battle over protecting the American flag continued into the 21st century as Congress attempted to pass a constitutional amendment prohibiting flag desecration.

In 2005 the House of Representatives voted 305-124 in favor of the amendment. The following year, however, in a 63-37 vote, the Senate fell short of the two-thirds majority required by the Constitution to send the proposed amendment to the states for ratification.

This article was originally published in 2009. Elizabeth Purdy, Ph.D., is an independent scholar who has published articles on subjects ranging from political science and women’s studies to economics and popular culture.