Following changes in the EU regulations, it became legal for bleaching to be undertaken by dentists and their trained team. However, restrictions remained on bleaching for patients under the age of 18. A revised position statement by the General Dental Council (GDC) determined that bleaching could be undertaken on these patients if it was wholly for the purpose of treating or preventing disease. The purpose of this paper is to discuss the safety, efficacy, indications and techniques for under-18 bleaching.

Following the 2012 Cosmetic Products Safety Amendment Regulations, it became legal for tooth whitening to be undertaken by dentists and their trained teams (dental therapist and dental hygienist) using tooth whitening material containing less than 6% hydrogen peroxide. 1,2 However, restriction on under-18 bleaching remained, limiting the use of whitening treatment for this group of patients to less than 0.1% hydrogen peroxide. This placed dentists in a precarious situation, with regards to clinical situations whereby bleaching was indicated, however, legally could not be provided.

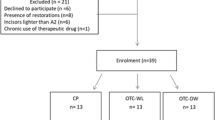

Ethically, these clinical dilemmas were only heightened by the knowledge that more invasive, direct and indirect restorations were permitted. No restoration is 100% successful. Crowned teeth may lose vitality in 19% of patients 3 and this may be more significant for adolescent patients due to the larger pulp complexes. Even the less destructive treatment modality of ceramic veneers has a finite life span, with a systematic review by Petridis et al. 4 noting that the most frequent complication of the restoration being marginal discolouration (9% at five years), followed by loss of marginal integrity (3.9–7.7%) at five years. The significance of these failures is also compounded by the younger age of these patients. Should a dentist introduce these young adolescent patients into the restorative cycle, simply to comply with EU/UK regulations, even though bleaching would be a more appropriate, less invasive and a less damaging treatment modality?

Thankfully, after lobbying from the British Dental Bleaching Society (BDBS) and the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry (BSPD), a revised position statement on the General Dental Council's (GDC) website was released stating: 'Products containing or releasing between 0.1% and 6% hydrogen peroxide cannot be used on any person under 18 years of age except where such use is intended wholly for the purpose of treating or preventing disease.' 5

Despite this, many have argued that legal advice should be sought from indemnity providers before undertaking bleaching treatment on such patients. However, correctly identifying and appropriately treating disease fall well into the scope and everyday practice of general dentistry and as such is not necessary.

Further questions remain with regards to the safety, efficacy and clinical technique required for under-18-year-old bleaching. Furthermore, elaboration on the exact clinical indications covered by the GDC position statement were required. This article will aim to provide an evidence-based response to the unanswered questions on the topic.

Carbamide peroxide (CP), also known as urea peroxide, was initially used as an oral antiseptic agent and cleanser. In 1964, Benjamin Dickstein reported using CP to treat neonatal oral candidiasis. 6 Other earlier studies demonstrated CP's effectiveness on plaque control and gingival inflammation. 7,8,9 In 1968, it was this use as an oral antiseptic which led to the incidental discovery of bleaching by Dr Bill Klusmeier. 10

Nowadays, there is much research to support the safety of bleaching, 11,12,13,14 however, most of this research was conducted on adults and less on the adolescent patient. In 2005, the European Commission Scientific Committee on Consumer Products concluded that 'The proper use of tooth whitening products containing 0.1 to 6.0% hydrogen peroxide is considered safe after consultation with and approval of the consumer's dentist.' 15

One concern commonly raised regarding bleaching in the adolescent patient, is the risk of tooth sensitivity. Tooth sensitivity in adults during bleaching treatment is common, and has been reported between 15–65%. 16,17,18,19 Sensitivity is related to the easy passage of hydrogen peroxide through intact enamel and dentin (reaching the pulp in five to 15 minutes) 20 and to the bleaching tray, which causes sensitivity in 20% of patients. 21

It has been hypothesised that due to the proportionally larger pulp complexes in the adolescent patient, tooth sensitivity would be more prevalent during bleaching treatment.

However, many clinical studies have demonstrated that this is not the case.

Bacaksiz et al. 22 revealed that in-office bleaching using hydrogen peroxide at high concentrations (25% and 36%) could be undertaken safely on the adolescent patient. Furthermore, several randomised control trials by Donly have shown that tooth sensitivity was relatively minor in adolescent patients in comparison to reported sensitivity among adult patients, 23,24,25,26,27 despite greater than normal hydrogen peroxide concentrations being used (6.5%, 9%, 10%). This could be attributed to the increased enamel quantity and quality of the adolescent teeth and also to the larger pulp complexes in adolescent patients' teeth which allow faster recovery from the acute inflammation experienced during a sensitivity episode. 27 Importantly, the sensitivity experienced by the under-18 patients is manageable and does not deter them from completing the tooth whitening treatment. 12

Gingival irritation is another reported side-effect associated with adolescent treatment. 23,24,25,26,27 Gingival irritation is more common in higher concentrations of bleaching products and may be more common among strip-applied bleaching agent in comparison to tray-applied. 28 For most patients, gingival irritation is tolerable and is not a barrier to completing the treatment. An ill-fitting tray is usually the primary cause for the irritation and the problem is usually resolved by relieving overextensions of the tray. Furthermore, failure to wipe away excess whitening product may result in gingival irritation and therefore it is essential that this is clearly explained to the patient and their supervising parent on delivery of the tray. 13

Significant bleaching effects following treatment have been repeatedly demonstrated when compared to baselines in clinical trials. 23,24,25,26,27 There have been some suggestions that the bleaching success and rate of bleaching may be increased in the adolescent patient, when compared to the adult patient. This may be due to the increased permeability of the dentine and enamel and the diffusion flux experienced due to the anatomy of the younger enamel structure, which is more porous and permeable. 29 The young teeth have also had less time in the mouth to acquire stains or deposit secondary dentin. There may also be improved compliance resulting from social pressures experienced in the adolescent age group, however, there is currently no research on this theory.

The GDC guidance mentioned previously states that products containing or releasing 0.1–6% hydrogen peroxide can be used in under-18 patients, only 'for the purpose of treating or preventing disease'. 4 Guidance on the indications and conditions for adolescent bleaching have been listed in Box 1.

Some may suggest that discolouration may not fall under the classification of disease, however, it is prudent to understand the psychological and psychosocial effects associated with discolouration 30,31 and the emotional effect on a child resulting from delayed treatment of the discolouration. 32 Negative self-image due to a discoloured tooth or teeth can have serious consequences on adolescents. As such, treating discolouration and disease may aid in prevention of bullying and associated or resulting mental health conditions such as depression and suicide. 33 Furthermore underlying enamel quality or quantity defects commonly associated with the discolouration also renders the classification of disease appropriate.

It is essential that all treatment options are provided to the patient and parents seeking dental bleaching, including the option of no treatment. All risks and benefits associated with bleaching must also be discussed before commencing treatment and consent appropriately obtained. It should be expressed that further restorative treatment may be required post bleaching, for example microabrasion, resin infiltration and composite bonding where large enamel surface defects exist. 12,34

Various factors relevant to the patient's discolourations must be considered when determining the need and urgency for bleaching in the under-18 patients. Some of these are listed in Box 2.

Detailed history taking, initial examinations and appropriate radiographs are essential for accurate diagnosis, treatment planning and identification of risk factors and oral pathology. It is essential to identify any restorations in the aesthetic zone and explain to the patient that post bleaching these may no longer be a matching shade and thus are likely to require replacement. 35

Furthermore, discolouration, particularly intrinsic stains, may not simply be an aesthetic problem and bleaching may not be the appropriate or the best choice for treatment. 14 This will be discussed later in the article.

Bleaching treatment for the adolescent patient and patient groups is listed in Box 1.

As discussed previously, the psychosocial effects of discolourations can be extreme. Severe discolouration can result from numerous aetiologies, including but not limited to:

Fluorosis can be effectively bleached, as shown in Figures 1, 2 and 3. Bleaching is most effective in class 1 to 3 of the tooth surface index of fluorosis and as such alternative treatment may be required for patients with severe flurorosis. 36

Severe discolouration may require prolonged bleaching. 14 This can be seen in Figures 1a and 1b, whereby after three weeks of bleaching treatment, the brown discolouration had reduced, however, had not completely resolved. Bleaching treatment was prolonged for an additional seven weeks and this eventually resulted in complete resolution of the brown discolouration (Fig. 1c). The patient was delighted with the final result, despite the presence of the white lesions and as such chose no further treatment.

A range of enamel conditions result in discolouration and can be effectively treated with bleaching. These include but are not limited to:

White spot lesions have numerous aetiologies. 37 Some markings are chronologic in nature and appear as white lines that follow deposition of enamel such as amoxicillin or high temperature defects 38 which are shown in Figure 4. Bleaching treatment whitens the surrounding or background enamel of the white lesion, which reduces the contrast of the defect as demonstrated in Figure 5b. It has also been suggested that elevation of salivary Ph and flow rates following carbamide peroxide application 39 may alter the refractive index of the white spot by promoting remineralisation, however, further research is required.

Isolated white blemishes (Fig. 5a), can be aesthetically challenging for the young child and tooth bleaching or whitening is a simple way to eradicate these unsightly markings on the teeth. This may need to be followed by microabrasion or resin infiltration. In the patient illustrated in Figures 5a and b, a combination of bleaching using custom tray-applied 10% carbamide peroxide followed by resin infiltration was used to successfully to eradicate the white blemishes on the central incisors (Fig. 5b).

Original white spots may become more noticeable during bleaching treatment, as seen in Figure 1c. This is due to the bleaching material penetrating the weakest part of the enamel first, which is often the white spot. This commonly occurs during the first few days and is referred to as the 'splotchy stage' of bleaching. 40 The patient must be urged to persevere with the bleaching treatment to allow time for the bleaching material to dissipate equally throughout the enamel and allow efficient lightening of the background. The 'splotchy stage' must be described to the patient before treatment. This is essential for informed consent and to ensure compliance. 41

White spots that are present following completion of bleaching treatment may become less noticeable two weeks post treatment, as oxygen dissipates from the tooth and especially the white spot defect, however further treatment may be required to mask the defect. 34

Isolated yellow and brown stains result from numerous aetiologies. 12 Fluorosis may result in brown blemishes as seen in Figures 1a, 1b and 1c. Brown stains can be removed 80% of the time by bleaching alone and as such, should be the first line of treatment for such conditions. 42 Cases where bleaching does not completely remove brown staining should utilise additional microabrasion and bonding procedures. 43

Coronal defects can present as discrepancies in tooth shape, size, position, proportion, shade and number. Bleaching often forms an integral part in management of aesthetics and can reduce the need for invasive restorations in the management of such cases. No better is this illustrated in use of bleaching, bonding and orthodontics as compared to the use of porcelain veneers and crowns. Furthermore, the use of bleaching to lighten the value of a tooth, can reduce the requirement for excessive reduction required for indirect restorations to mask discolouration appropriately. This enables the use of more translucent, multi-chromatic restorations, thus improving the outcome of such treatment modalities. Validation of bleaching in such circumstances is particularly noted in severe tetracycline discolouration.

Bleaching material can also improve the longevity of restorations in the anterior region, which may be failing due to exposure of restorative margins or due to discolouration of underlying tooth structure. Although bleaching materials have no effect on porcelain, they can successfully penetrate and bleach tooth structure beneath porcelain veneers. 44

As is true for all bleaching cases, further restorative treatment should be delayed for at least two weeks following the completion of bleaching. Bond strength to composites is reduced by 25–50% during bleaching, 45 however, returns to normal two weeks following treatment. This results from oxygen, in the enamel because of the bleaching material, inhibiting the set of resin tags in etched enamel. Over a two-week period, the oxygen dissipates out of the enamel thus returning bond strength to normal.

Oxygen present in enamel can also lead to incorrect shade taking and thus, shade taking should also be delayed by at least two weeks and up to six weeks in cases whereby exact shade matching is at a premium.

MIH lesions often present as demarcated enamel opacities ranging in colour from creamy white to yellow/brown, as seen in Figure 6. It is well documented that children with MIH may suffer from a reluctance to smile or a lack of confidence due to the appearance of their teeth and thus may require treatment early to prevent this. 46 Bleaching has been reported to produce some improvement in MIH patients, especially with the yellow brown discoloured defects. 47

Teeth affected by MIH show inflammatory changes within the pulp 48 and as a result, sensitivity is more common among this group of patients. Therefore, adequate sensitivity prevention before undertaking bleaching treatment is required.

Several hereditary conditions can lead to white blemishes and white discolouration of teeth. These markings can be generalised for example in amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) patients (Fig. 7) or there can be a single isolated white mark or white blemish on a tooth. Depending on the severity, tooth whitening can be undertaken as the first option for this group of patients.

Hereditary conditions associated with defects in enamel and dentine include:

1. Hereditary conditions associated with defects of epithelial tissues: 49

2. Hereditary conditions associated with defects in mineralisation pathways:

3. Dentinogenesis imperfecta 54

4. Amelogenesis imperfecta: 55

5. Cystic fibrosis 56

Bleaching has been shown to be successful in the minimal invasive treatment of hereditary conditions especially amelogenesis imperfecta 57 and dentinogenesis imperfecta. 54 This is extremely beneficial for such patients as preservation of existing enamel is crucial in such conditions. Sensitivity may also be an issue for patients with hereditary defects and adequate sensitivity prevention is required.

Discolouration associated with trauma or loss of tooth vitality can be very severe and range in colour from yellow, black, brown, purple and grey (as seen in Figure 8).

Haemorrhage of the pulp is the most common cause of discolouration after trauma. Blood enters the dentinal tubules and then decomposes leading to a deposit of chromogenic blood degradation products, such as haemosiderin, hemine, haematin, and haematoidin. Chromogenic degradation products also result from pulp necrosis. 58

Calcific metamorphosis may also results in discolouration and is commonly seen as early as three months after traumatic tooth injury. It is characterised by the deposition of hard tissue within the root canal space and a yellow discolouration of the clinical crown. 59

Discolouration may result from iatrogenic induced causes following treatment of the non-vital tooth. These include:

It is essential that iatrogenic causes are appropriately identified and managed before commencing with bleaching treatment.

Discoloured teeth with a history of trauma should undergo vitality testing and if no previous radiographs have been taken, appropriate radiographic assessment should be undertaken to ensure appropriate treatment is undertaken prior to and post bleaching. 62

A single discoloured tooth which retains vitality, for example in calcific metamorphisis, 59 should not have elective root canal treatment undertaken. These patients should rather be provided with a 'single tooth' bleaching tray as seen in Figure 9 and bleaching agent applied externally, solely to the targeted discoloured tooth. This is because externally applied bleaching material diffuses readily through teeth and uniformly changes dentine shade throughout, regardless of depth. 63

There are several different non-vital bleaching techniques and these have been described elsewhere in the literature. 64,65 The author would recommend the inside/outside closed bleaching technique for the adolescent patient. This involves sealing 10% CP into the pulp chamber and providing the patient with a 'single tooth' bleaching tray, who continues bleaching externally at home. This technique allows for adequate cleaning of the pulp chamber without the associated risks of leaving the access cavity open and allows repeated frequent application of bleaching agent externally, thus allowing maximum whitening of the tooth without the patient returning to the practice.

Some may choose to utilise the inside outside open technique. This would involve leaving the access cavity open to allow frequent replacement of the bleaching agent intracoronally, which would otherwise become inactive up to ten hours post application. As mentioned previously, this is unnecessary due to the rapid penetration of bleaching material through the tooth from the external surface. Furthermore, this may also potentially jeopardise the root canal treatment, if the patient fails to keep the access cavity appropriately clean or fails to return in a timely fashion for the access cavity to be closed. As such, this technique should only be used on well-motivated patients who are excellent attenders and with excellent oral hygiene.

Numerous systemic diseases can lead to discolouration including but not limited to:

Antibiotics used to treat systemic infections, such as tetracycline, 69 amoxicillin 38 and ciprofloxacin can also lead to discolouration of teeth. The discolouration experienced as a result of systemic disease is most likely to be intrinsic in nature and, as such, requires prolonged bleaching. Tetracycline staining has been shown to require up to six months of prolonged custom tray-applied 10% CP bleaching to ensure a satisfactory effect. 69 This whitening effect has been shown to remain in 60 and 90-month follow up studies. 70,71

Indications for bleaching in under 18-year-old patients:

Considerations

The shade of the discolourations:

Discolourations should be classified based on severity, as mild, moderate and severe: moderate and severe discolourations warrant bleaching treatment

The extent of the discolourations:

Discolourations may be uniformly spread throughout the dentition, limited to a few surfaces such as in MIH, or limited to a single surface/ tooth following trauma

The colour of the discolourations:

Grey, brown, black, orange, deep yellow

The impact of the discolourations on the child:

Is the child aware of the discolouration? Does the discolouration impact the child's life? Is the child bullied by their peers as a result of the discolouration?

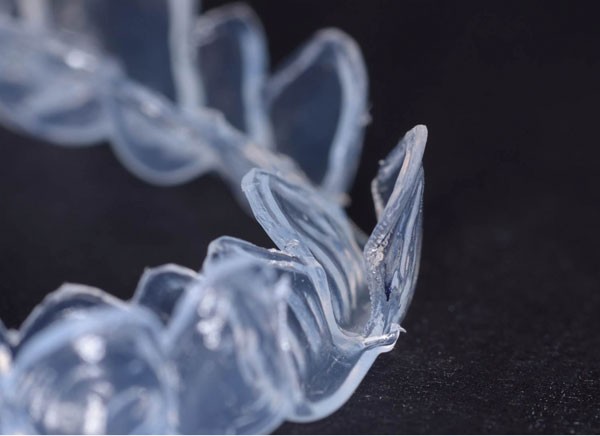

Haywood has recommended commencing bleaching in adolescent patients at ages 10–14, 40 however, this should still be assessed on an individual basis as discussed earlier (Box 2). A close fitting, non-reservoir, custom tray is recommended for these patients to minimise the amount of bleaching material. 72

Carbamide peroxide (CP) is the recommended bleaching product for under-18 patients. This is due to the additional urea having beneficial cariostatic effects and an antibacterial effect which have been shown to improve gingival scores. 40,73,74,75 This would be of extreme benefit to the patients listed in Box 1, who commonly suffer from poor gingival health resulting from a lack of motivation or sensitivity. Furthermore carbopol, a slow oxygen releasing agent present in 10% CP, results in a steady slow release of oxygen making the process sustainable through the night. 76

There were initially concerns that wearing beaching trays could impede tooth eruption. Although no research has been undertaken assessing this, current orthodontic opinion is that such trays do not impede eruption and can be safely used for the short time required for bleaching.

The best tray design for under-18s would be vacuum formed, custom made, non-reservoir, close fitting trays made from 0.35 mm soft acrylic. With regards to scalloping design, this is based on clinician's preference. Some clinicians prefer to scallop the tray to avoid any soft tissue contact of the bleaching material with the gingiva. However, extreme care is needed in the tray fabrication to avoid jagged edges on the tray which discourage compliance. There is a greater chance of leakage of material if not well made, so only a minimum of bleaching material should be inserted into the tray. Reservoirs or spacers have been shown to be unnecessary. 77

A non-scalloped tray design tends to seal better against the soft tissue, and be more comfortable to wear. Although it would allow the 10% carbamide peroxide to contact the tissue, the CP material is made to contact tissue. The original intent of 10% CP was as an oral antiseptic for wound healing of soft tissue, so generally there is no negative consequence for tissue contact. Should there be any issues, those areas of the tray can be shortened to the scalloped design.

Custom trays should be worn for a minimum of two hours under parental supervision. Either daytime or overnight wear is acceptable, however, as CP can remain active for up to ten hours, 78 overnight use is recommended for maximum benefit.

Generally children with malformed or discoloured teeth are very motivated to remove the defect, so comply with treatment very well, especially under parental supervision. If compliance is an issue, treatment should not be undertaken.

As discussed previously, sensitivity from bleaching treatment is common and this must be explained to all patients before undertaking treatment. In the majority of bleaching patients, history of sensitivity is the greatest predictor for sensitivity during treatment 79 and as such a detailed sensitivity history is required on initial patient examination.

However, for certain groups of patients predisposed to sensitivity such as patients with MIH, AI and other hereditary defects, adequate sensitivity prevention before undertaking treatment would be beneficial. Prevention may be in the following forms:

If sensitivity is experienced during treatment, two approaches can be undertaken. A passive approach could be taken, whereby the frequency of application of CP or wearing time is reduced. Alternatively, an active approach, employing the use of desensitising agents either in the custom tray or applied during brushing (as described in prevention).

Sensitivity resulting from wearing of the bleaching tray alone, as mentioned previously, is commonly associated with the mechanical pressure of an improperly fitting tray, from occlusion on the tray, and is more common with harder bleaching trays. It is therefore essential that an accurate impression is made and a soft tray is used to prevent or alleviate the tray associated sensitivity.

Tooth bleaching continues to be one of the cornerstones of minimal intervention aesthetic dentistry. Its use, having previously been limited to the over-18 patients, can provide adolescent patients with good aesthetic results, minimal side-effects and minimal safety concerns. Furthermore, effective tooth whitening results can improve patients' self-esteem, self-confidence and can help address key psychosocial issues associated with discolouration.